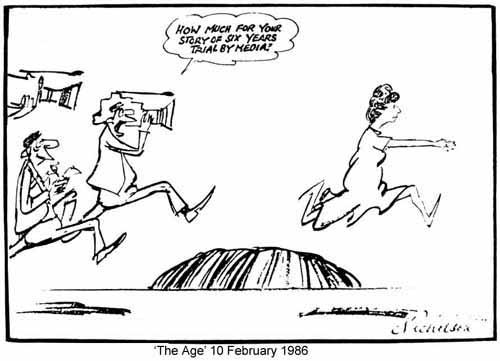

There has been much criticism about chequebook journalism from the media themselves, and others, so I think it deserves discussion.

Simply put, most media worldwide is a ‘for profit’ business. Their owners, outside of small-town media outlets, are generally among the wealthier people in their community, in some cases the wealthiest in their entire country. The reporters and ‘faces’ we see on television are paid as well, some quite handsomely. As noted in other sections, the name Lindy has made millions of dollars of profit for the media owners. If the media want to report the news, then they are free to do that; indeed, ‘news’ should not be paid for. When people are offered money to say something in an interview, then there can be mixed motives; you would have to wonder if they were telling the truth, or saying what they did because they knew that it would bring them money.

During Lindy’s case, very often the only ones giving out interviews – was it salacious gossip, or news? – was the Northern Territory government, even though the ‘news’ was Crown point of view – that Lindy had murdered her daughter. Because of the way the Crown ran the case after the first inquest, the Chamberlain’s defence had very little idea what the Crown would say, or what witnesses the Crown would call until they saw it happen in the courtroom. The defence did not give interviews, because doing so would give the Crown a further unfair advantage. In fact, the Chamberlains did give many unpaid personal interest interviews before Lindy was released from prison but had found that the printed, or edited for television interviews did not portray accurately what they felt was important. It was of critical importance to Lindy that the interview be accurate, as so many rumours and lies had already been told by others.

By the time Lindy was released from prison, the Chamberlains were many millions of dollars in debt, and were too well known to be employable in the traditional sense. Plus, they were still convicted criminals, and had the Royal Commission ahead of them. As it turned out, they also had another NT Supreme Court case, compensation application, and a further inquest to pay their legal team to prepare for as well. One way that they felt they could pay their legal bills, and make sure that the media reported their view accurately, was to charge an interview fee. It was not they who came up with the idea, but the media themselves. It appealed to the Chamberlains on the financial front, of course, but more importantly, they would have some control of how the media reported what they said. With a contract, even if it is only for a dollar, then there is an agreement on how both sides will behave, and is generally honoured.

It should not be thought that all media people are dishonest or intentionally malicious. They are not, and there are some fantastically ethical, caring people in all areas of the media. There is a lot of pressure to get the news out, and it is a constantly changing environment – one where misunderstandings or even outright sloppy work, can slip through under severe deadline pressures. Sometimes the reporters themselves do not have the luxury of time to do the job as well as they’d like. On other occasions, an editor makes changes which the reporter knows nothing about until it is already printed, or a caption writer needs to make the headline catchier, so that people will be attracted to buy the paper or watch the show. If an error is made, then tomorrow is another day, and another lot of news. An apology, when one is ever given, is usually too small to read, and buried well within the paper.

One media personality credits the fact that the Chamberlains got paid for their first interview after Lindy got out of prison with being the start of chequebook journalism being more and more accepted. That same person is one that Lindy has refused to do further interviews with, as they persistently asked her questions on air about her personal life in a supposed ‘news’ interview. The questions asked were not relevant to the interview, were not news in the sense of what the interview was supposed to be about, and most importantly, were on a topic that the interviewer had agreed not to question her about. She had been delayed on her arrival to the studio, and had received devastating news moments before she walked onto the set. When she confronted the interviewer afterwards about his tactics they merely replied, “That’s showbiz.” Those who control the mouthpieces – the media – should be more ethical than that, especially when they claim publicly to be.

When Lindy was released from prison all of the media were bidding fast and furious to interview the Chamberlains, and it was they who first waved money around. The behind-the-scenes manoeuvring would make very interesting comedy. A joint interview between Australian 60 Minutes and Australian Women’s Weekly was ultimately selected. The supposed fee for that interview has been mentioned many times in the media and in books. What is not mentioned is just as important: The Chamberlains were later told that that interview was worth a minimum of four times what they had accepted; the Chamberlains had had huge expenses, and their church had supported their legal costs, which had been nearly $5 million dollars at that stage. They immediately gave the entire sum to the church to help begin paying back their debt, only to later find out that they had to pay 48% of the money in taxes – money which they no longer had!

The news is reporting of an event, which can also include someone’s viewpoint. With the public interest in the Chamberlains it had got beyond the news and had become more like entertainment. Why else has it been the ‘current events’ shows, and women’s interest magazines who want to speak with Lindy the most?

She always spoke to the news reporters after an event, such as the inquest in Darwin in 1995, which she did immediately in front of the courthouse. She gave them her statement, and some quotes for the papers or soundbites for the television crews. More than that becomes ‘entertainment’.

Since the magazines and television programmes are making money from selling her story, and asking her to sit for photos and provide interviews, is it unreasonable that they should share some of it with her? She is so well known in Australia that it is virtually impossible for her to get the kind of job the rest of us take for granted. (We could move to another country where she is not as recognised, as we did for a few years, before returning to be near Aidan, and Lindy’s parents in their older years. But you shouldn’t have to leave your own country just to overcome prejudice and be able to earn a normal income.)

But, if they want Lindy to give her time to them – which can take 2-3 days for what gets edited down to 20 minutes on television, or a week for a two or three page article – then it seems reasonable that she be paid for that. No media outlet is going to pay Lindy for any interview that will not make them far more money than it cost them. They are not in business to loose money. If Lindy’s name did not sell their programme, magazine, newspaper, or book, they would not want to talk to her.

Even if it were the case that she could easily find way to earn an income, does that mean that she should offer her time so that someone else can make the profit? None of us would work for someone on that basis, including reporters! That sort of logic is as faulty as that of two people standing before the judge at a divorce settlement. For years the couple has split their family income 50/50. One has saved and invested, and the other has spent almost everything on things that don’t last. Is the one who has almost nothing left at the time of divorce entitled now to take half the assets the other saved and scrimped for? Of course not.

Twenty-one books about the case have been written and sold well, including Lindy’s own. When the rights to John Bryson’s book Evil Angels was purchased from him to create the Hollywood movie (the film was called Evil Angels in some places, A Cry in the Dark elsewhere), the Chamberlain’s were offered a chance to provide information on the personal side. But any income they got from that was just for the time they spent consulting with the writer, director, and actors. This is how Lindy wrote about the impact of the film, in her book:

I did a lot of my shopping in the Queen Victoria (outdoor) markets in Melbourne or the Vic Boutique, as it is often known. I was able to bargain like anyone else, until publicity on the film started. (Why is it that everyone automatically thought we were instant millionaires just because John Bryson sold his book rights?) When I went again during that time, one of the ladies at the ‘Vic’ looked at me and said, ‘How about this for you?’

I said, ‘No, far too expensive.’

She just laughed and said, ‘You can afford that, you are rich now.’ Slowly the idea continued to be perpetrated that because a film was being made about us, we were rich and could afford anything we liked. My bargaining power in any given situation was virtually nil after that, and we read all sorts of stories about what we had done, or were supposed to be doing.

Everyone seemed to overlook the fact that is was John Bryson’s book that the film was based on. We only helped with extra research on the personal side. For some reason people think that if a book or something is about you, you get the profit. The author gets the profits and they don’t even have to ask your permission to write about you-or to make a film. If they want to they can take the chance of being sued for libel, and just do it. If you have been convicted of a crime anyone can write libel or outright lies about you whenever they like, as some did to us, and you cannot touch them. There is no recourse, even though we have been cleared.

(Additional Note: under Australian law, the convicted person looses their civil rights; anyone can say the most heinous untruths about them, and they have no legal rights to stop that happening. Some of the books and articles written while Lindy was in prison could not be printed after her exoneration, as they were full of known lies.)

Opera Australia graciously allowed us to attend several operas the year that the opera Lindydébuted, which we greatly enjoyed, but we were not paid for any of our consulting. The 2004 television mini-series was titled after Lindy’s book Through My Eyes, as they purchased the rights to the book, upon which they were to base the mini-series. She also consulted to the producers, but was just one of what we were told were more than three hundred consultants. Even though it may have been promoted as her true story, if you read her book, and compare it to the mini-series you will find significant differences. By contract, it is the producer who has the final rights as to what is shown on the screen, not Lindy. Lindy gave enormously of her time and effort, sharing insights they would not have gotten any other way. Doesn’t she deserve to get paid something for it as well?

Ironically enough, many times those complaining most loudly about chequebook journalism were the ones who had just been declined – and in more than one case, it was because of their unethical ‘behind the scenes’ behaviour. The accepted bidder for a story – and yes, it can be like an auction – is not necessarily the highest bid. Lindy is always mindful of the ethics of the organisation as well as that of the reporters, researchers, and editors or directors used. Even considering all of that, you can still mis-judge a person.

The ethics of chequebook journalism can be rather shady too. In a story we know connected with this case, it was continually claimed publicly that the individual involved was not being paid for the story. Perhaps not, but it is possible to pay members of a person’s family, some of their bills or a mortgage, for their lawyer, or a holiday – all so that the person involved can legally say that they have not received payment. There are many ways to stretch the ‘technical’ truth, but the intention is still to mislead. It is legal, but not morally correct.

Only by critical reading or viewing can we, the public, ensure that the ‘news’ is actually news – unbiased and factual – and that it is not entertainment dressed up as news, but really appealing to our natural interest in the sensational.

More Information:

- Related newspaper article

- Since we are discussing money here, just a note on compensation

- Cartoonist Peter Nicholson’s website: www.nicholsoncartoons.com.au